Background

For summer 2019, I relocated to Pittsburgh to work in Carnegie Mellon’s Human Computer Interaction Institute (HCII) as a UX research intern. Working closely with Dr. Aniket Kittur and his team of talented researchers, I assisted in developing Fuse: a chrome extension to help researchers collect and organize information.

This video shows an overview of our extension and the potential it holds for supporting sensemaking throughout various stages of the research process. To download the fuse extension, visit the Fuse website at getfuse.io.

My contributions throughout the summer revolved around three key projects:

Onboarding Design and Testing

Storyboarding for Prospective Feature Development

“Getting Information Out of Fuse” User Research

I’ll explore each of these projects in greater detail below.

Onboarding Design and Testing

My biggest project during my summer on the Fuse team was the start to finish design and testing of a new onboarding sequence. In past versions of Fuse, there had been no onboarding procedure besides a pop up message encouraging new users to “try capturing and saving content”, so this was a first effort at designing an onboarding sequence to introduce users to Fuse.

To approach this task, I began by researching various styles of onboarding. After reading up on situations where different onboarding strategies were more or less successful, I thought about situations in which users would be introduced to Fuse. In comparing my research to the situations in which users would first encounter Fuse, I decided to design a Trello-style onboarding. Trello, a web based list making application, onboards users by dropping them into an already created Trello board and allowing them to explore the functionality, rather than stepping them through a tooltip based onboarding sequence. This style of onboarding intends to avoid overbearing explanations and allow users to jump into learning through organic interactions with the tool.

This onboarding project’s design underwent three major iterations, with modifications based on observation from usability tests with 2-3 subjects. After creating a basic first draft of the design, I approached users in a coffee shop on Carnegie Mellon campus and asked them to try out a tool I was helping to build. I would give them my computer and allow them to explore the onboarding project, noting the functionality they did and didn’t discover, and asking questions to clarify whether their understanding of the was in harmony with the tool’s actual capabilities. Through these user tests, I gained insights that spurred modifications in the next iteration of the design, a process thoroughly documented in the insights document for this project, accessible below.

Overarching themes in the successful development of this project included finding a balance between too much clutter and too little information, user difficulties with understanding ways to organize their information, and strategic use of GIFs. The first draft of my design was far too information heavy, with multiple GIFs on screen at the same time overwhelming the user and scattering their attention. In the second draft, where I took out all GIFs, users were at a loss for where to direct their attention. Although this was a pressing problem, it allowed me to discover other interface concerns, such as user difficulties with understanding ways to organize their information. In the final design of the onboarding project, I reimplemented GIFs, but did so more strategically to draw users’ attention to certain parts of the screen, moving them through the onboarding project without explicitly using a tooltip sequence. This clarity of direction through the project, alongside other informed modifications, helped resolve the less obvious user challenges that had emerged in the second round of testing. For example, although users still showed initial confusion about the various ways to organize their information, by the end of onboarding they showed greater understanding of the multiple ways to view and organize their cards and could demonstrate the interactions to organize information in those varied ways.

The below video shows the completed onboarding project, and the way a user might scroll through it and interact with the information at first glance.

When testing iterations of this project for revision with users, time constraints required an optimization to gain the most meaningful insights from the fewest users that could reasonably be tested with. Under these limitations, I was determined to still test thoroughly enough to reveal major limitations and user pain points in the onboarding process.

To achieve this aim, I designed the interview protocol to target understanding user mental models of Fuse’s overall structure, how certain interactions relate to each other, and the hierarchy of elements in the application. Gathering this information required a lot of probing with interviewees, but ultimately resulted in better understanding of user goals and expectations upon moving through the onboarding process.

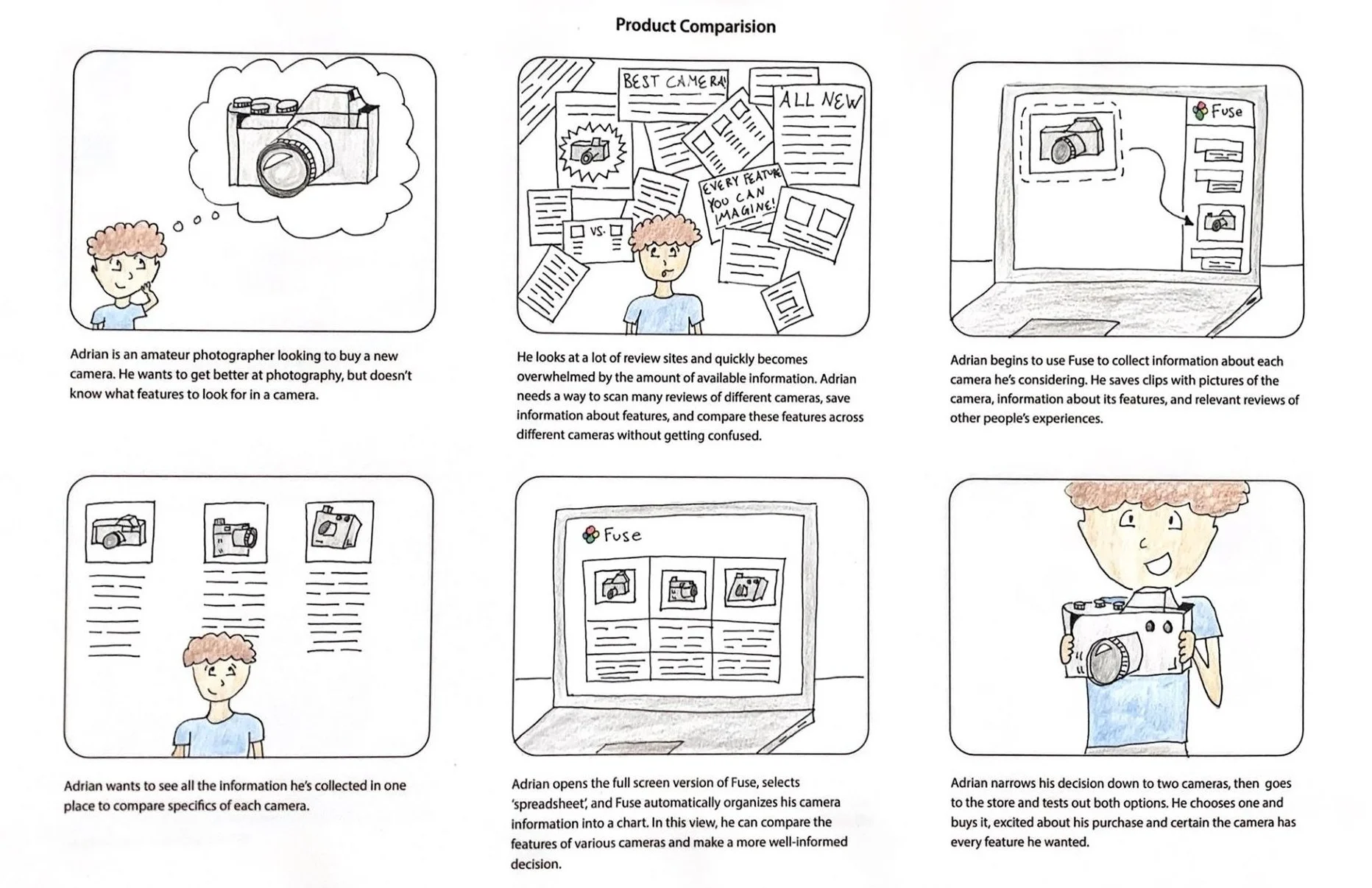

Beyond the introductory onboarding project, I also decided to create several ‘example’ projects typifying the key use cases we expected with Fuse. These projects were intended to allow users to see the different ways they can organize information in Fuse. use Fuse. The three projects I created were:

A product comparison example project (comparing different wireless headphone brands)

A trip planning example project (showing a completed Fuse project planning a family vacation to Hawaii")

An academic research example project (showing how a researcher might organize and save sources for a literature review)

When a user opens the Fuse sidebar for the first time, they’re dropped into the onboarding project, but their sidebar also contains these three example projects for them to freely explore and practice using Fuse in. The below video shows the way a user might scroll through the product comparison example project.

The introductory onboarding project and example projects are currently the user’s first in-application interactions with Fuse. To explore this onboarding experience yourself, visit the Fuse website and download our chrome extension.

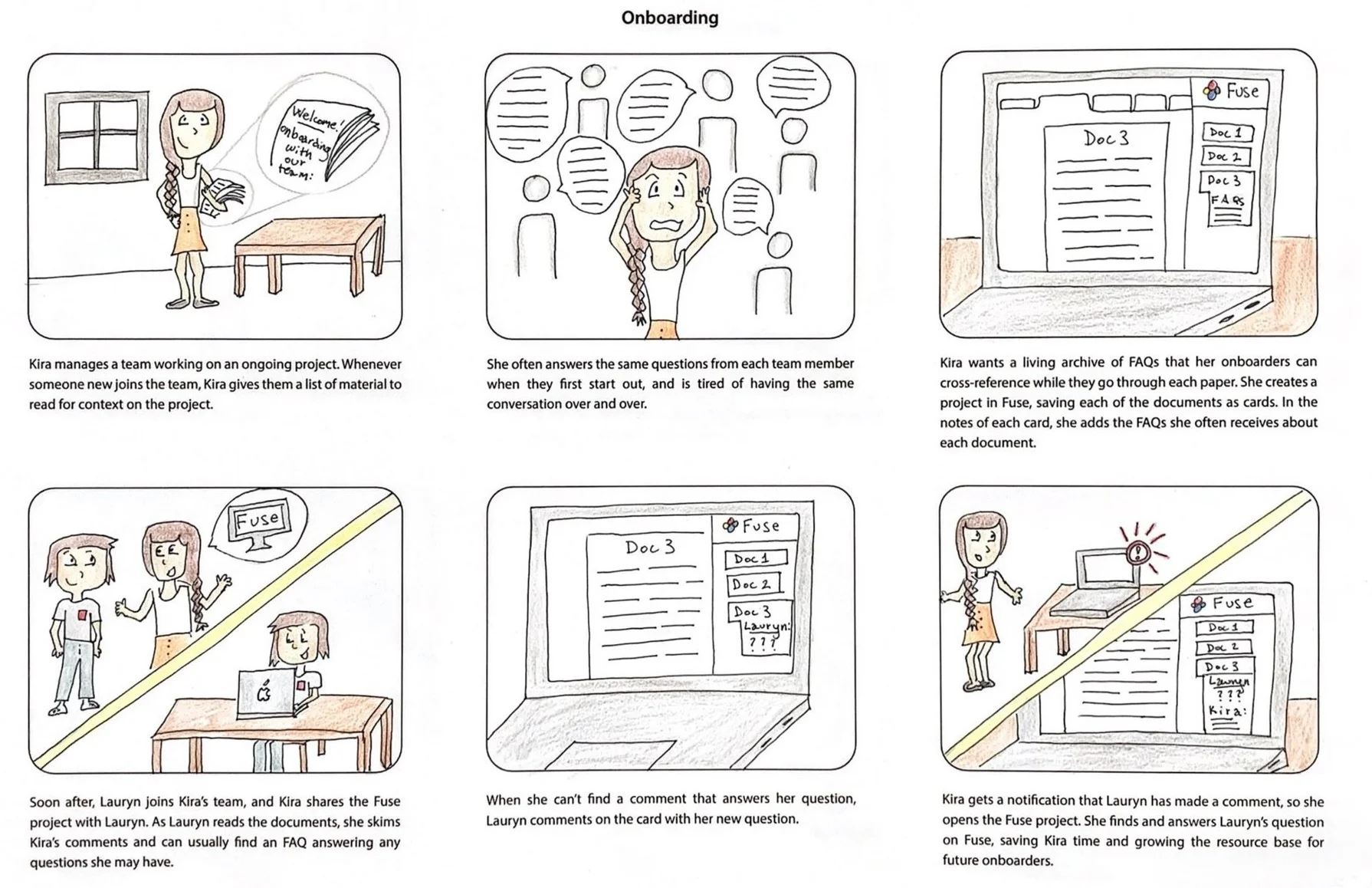

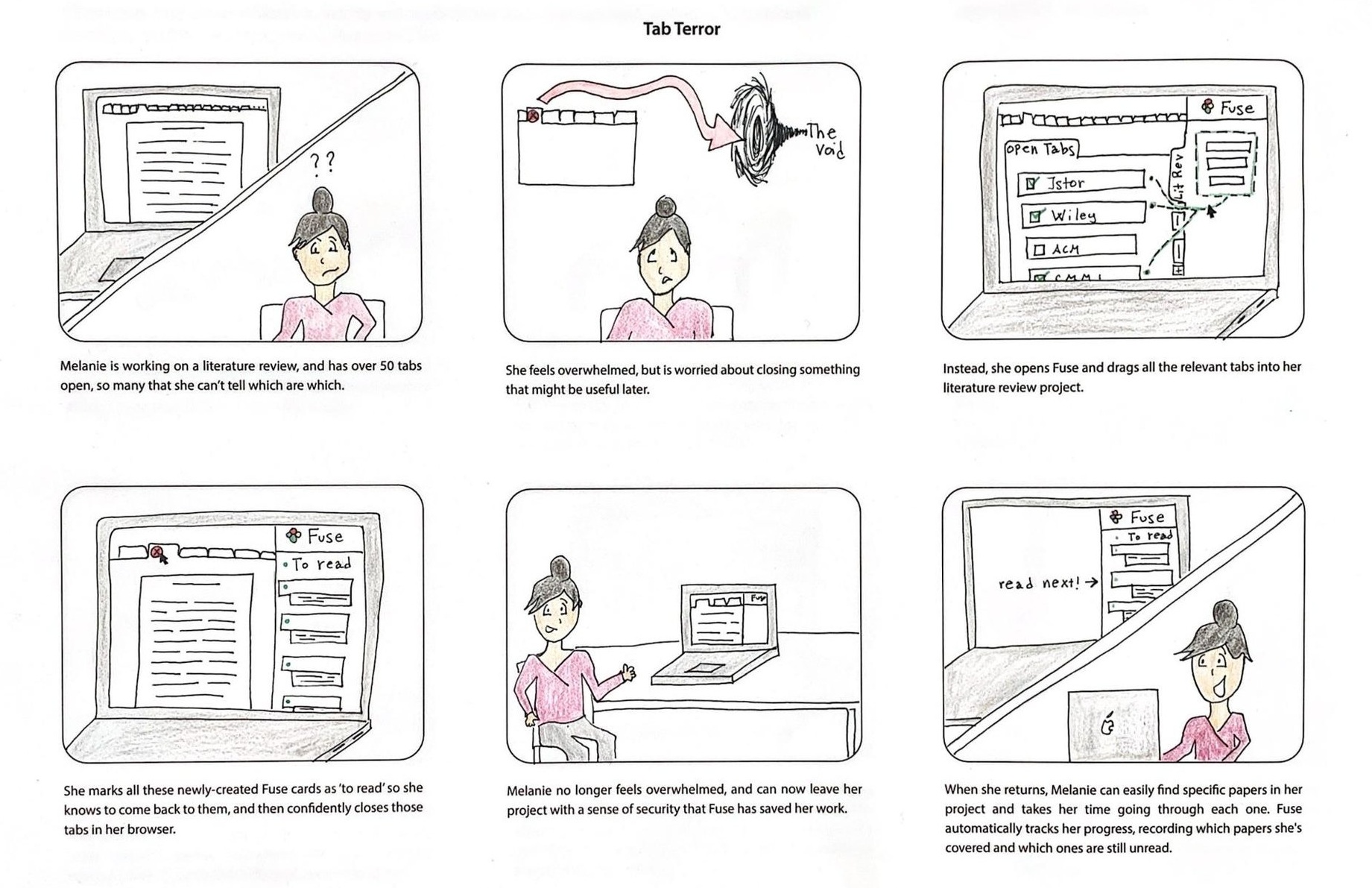

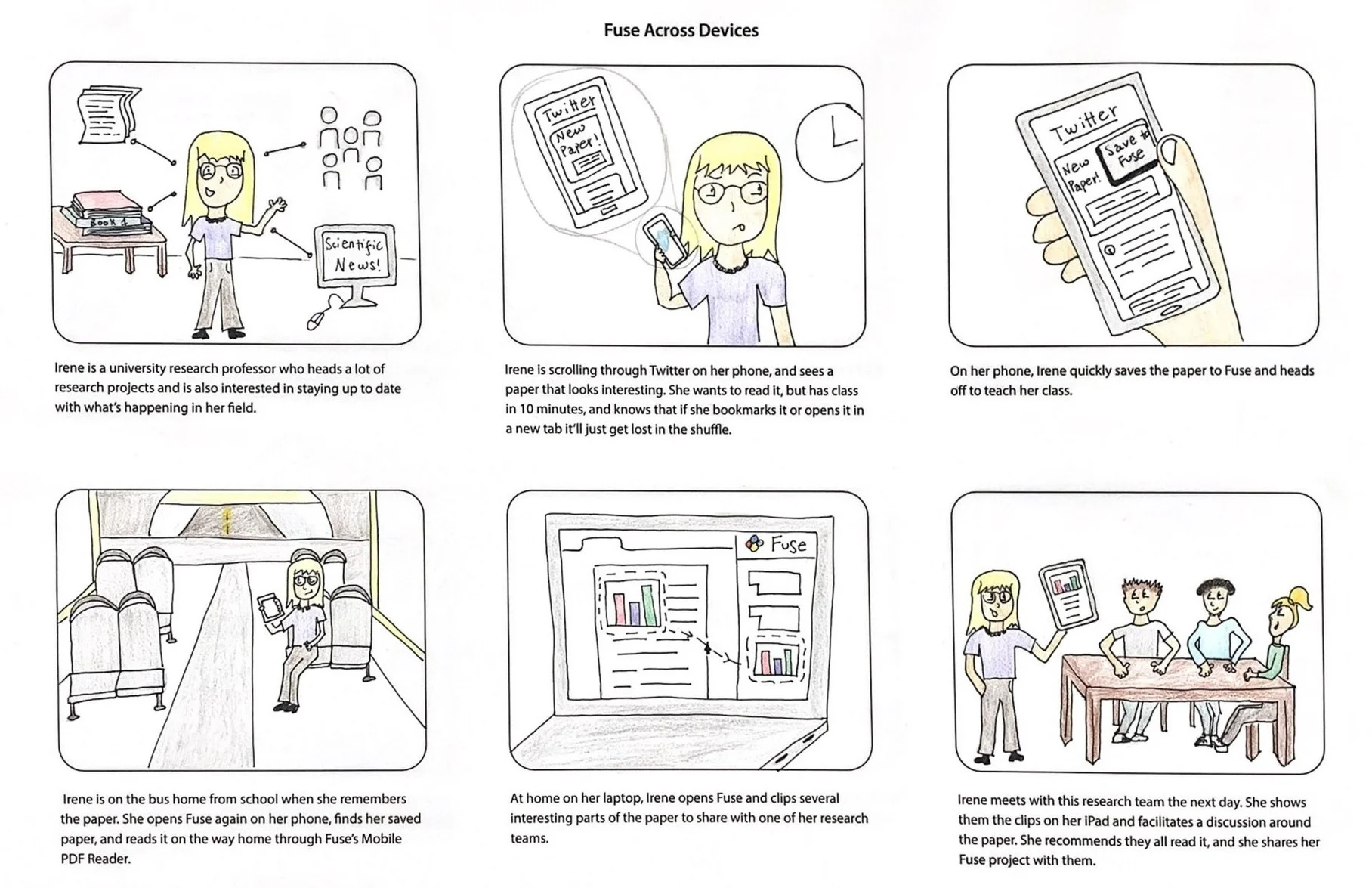

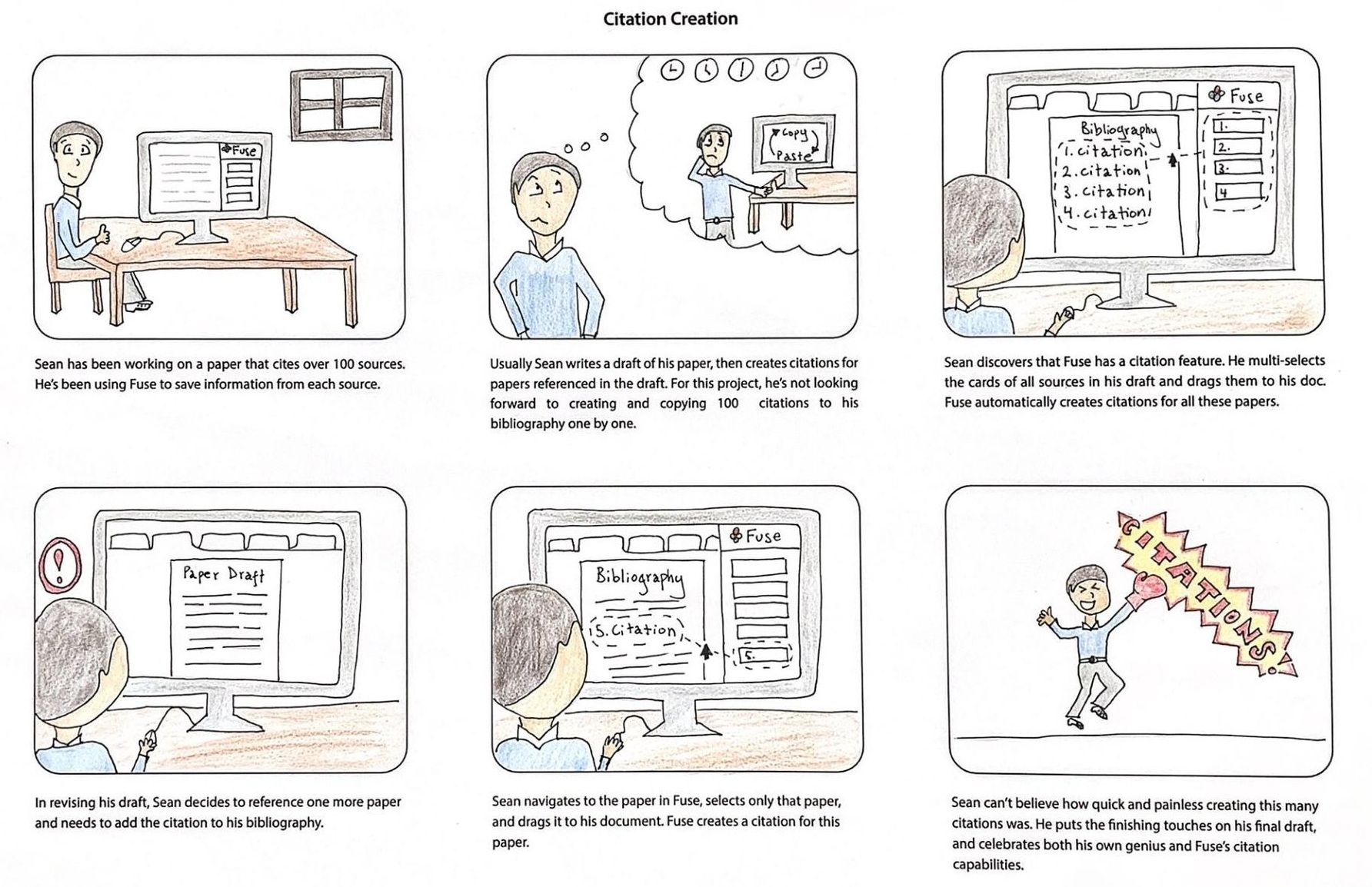

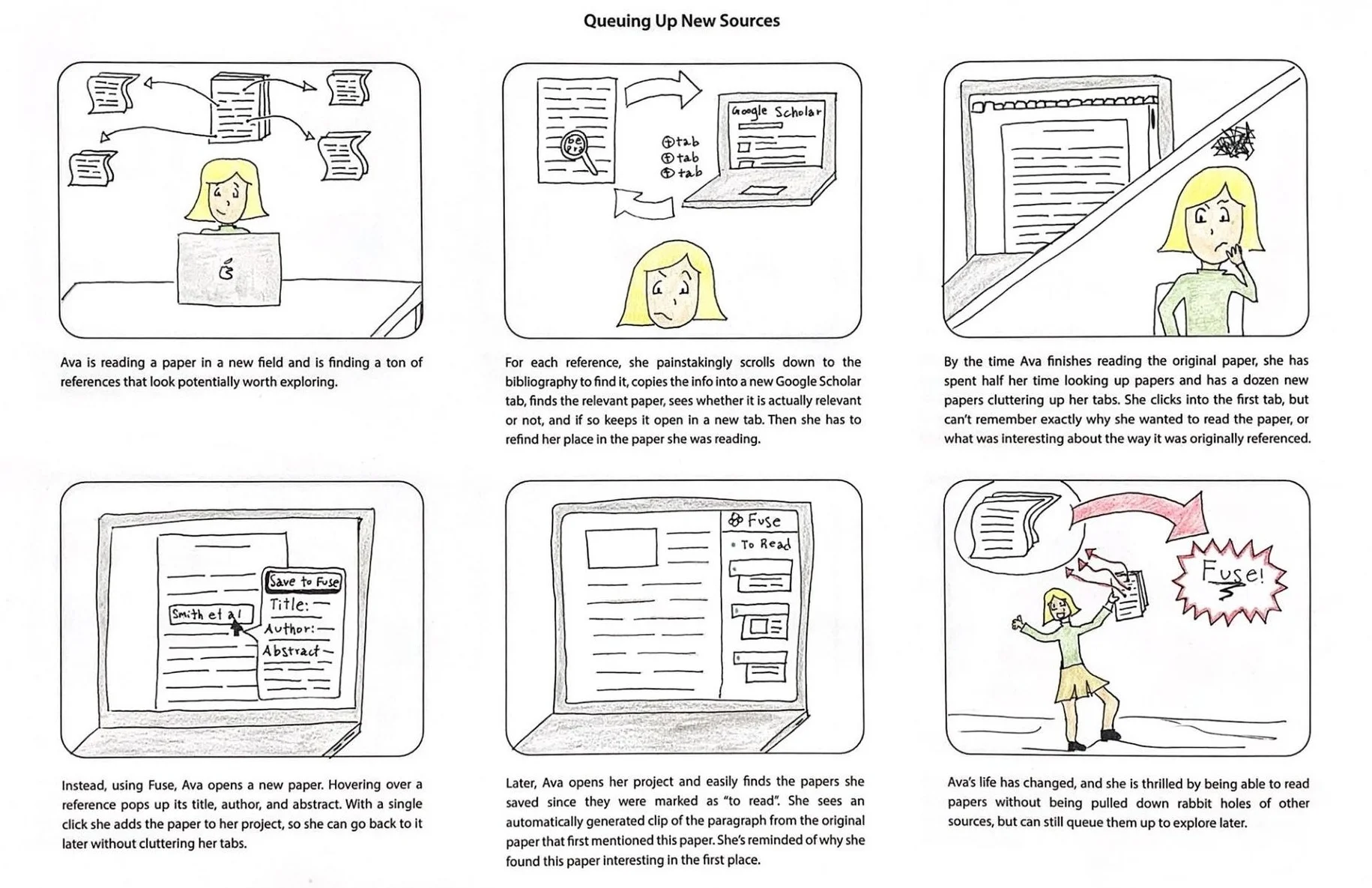

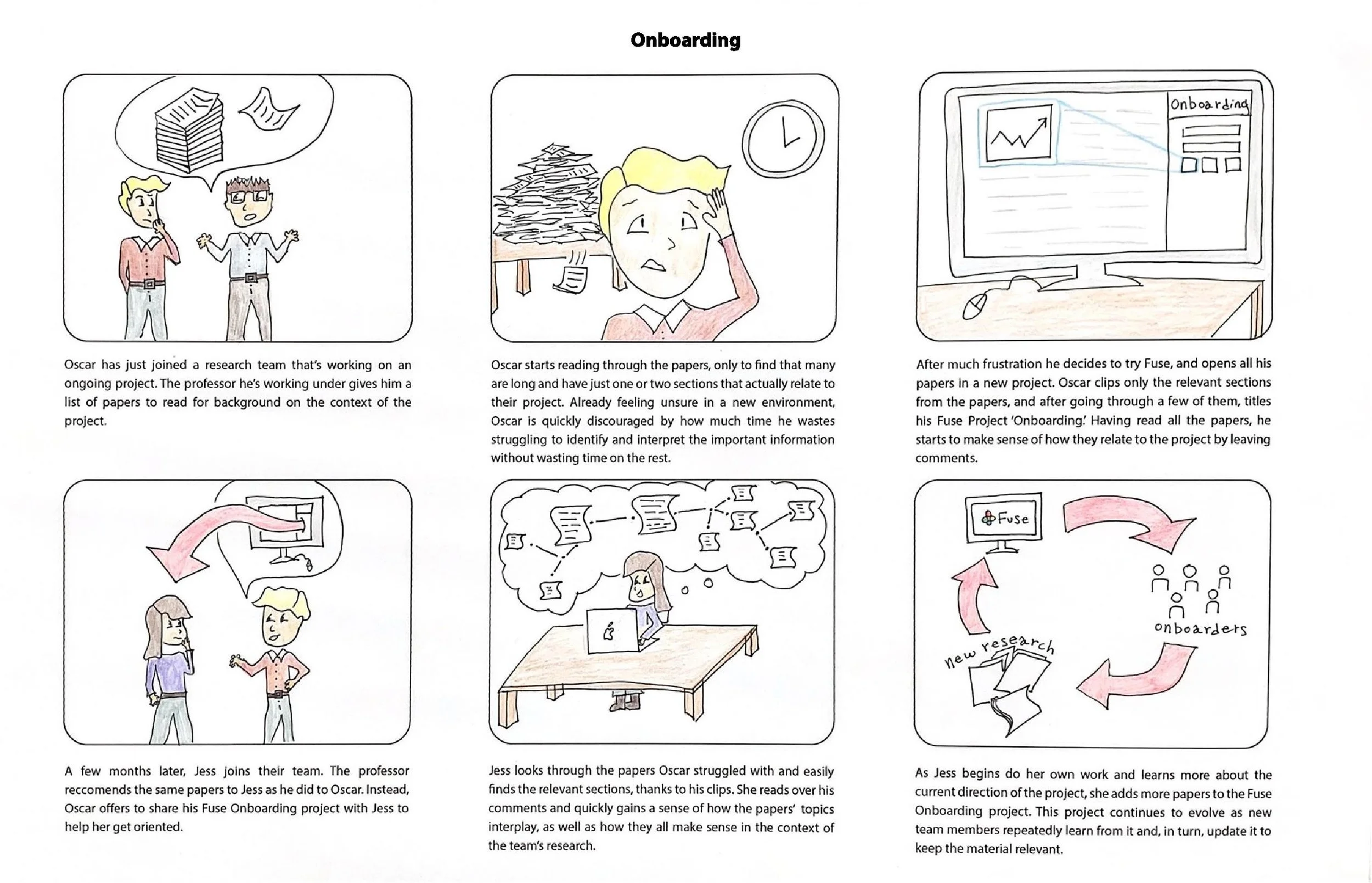

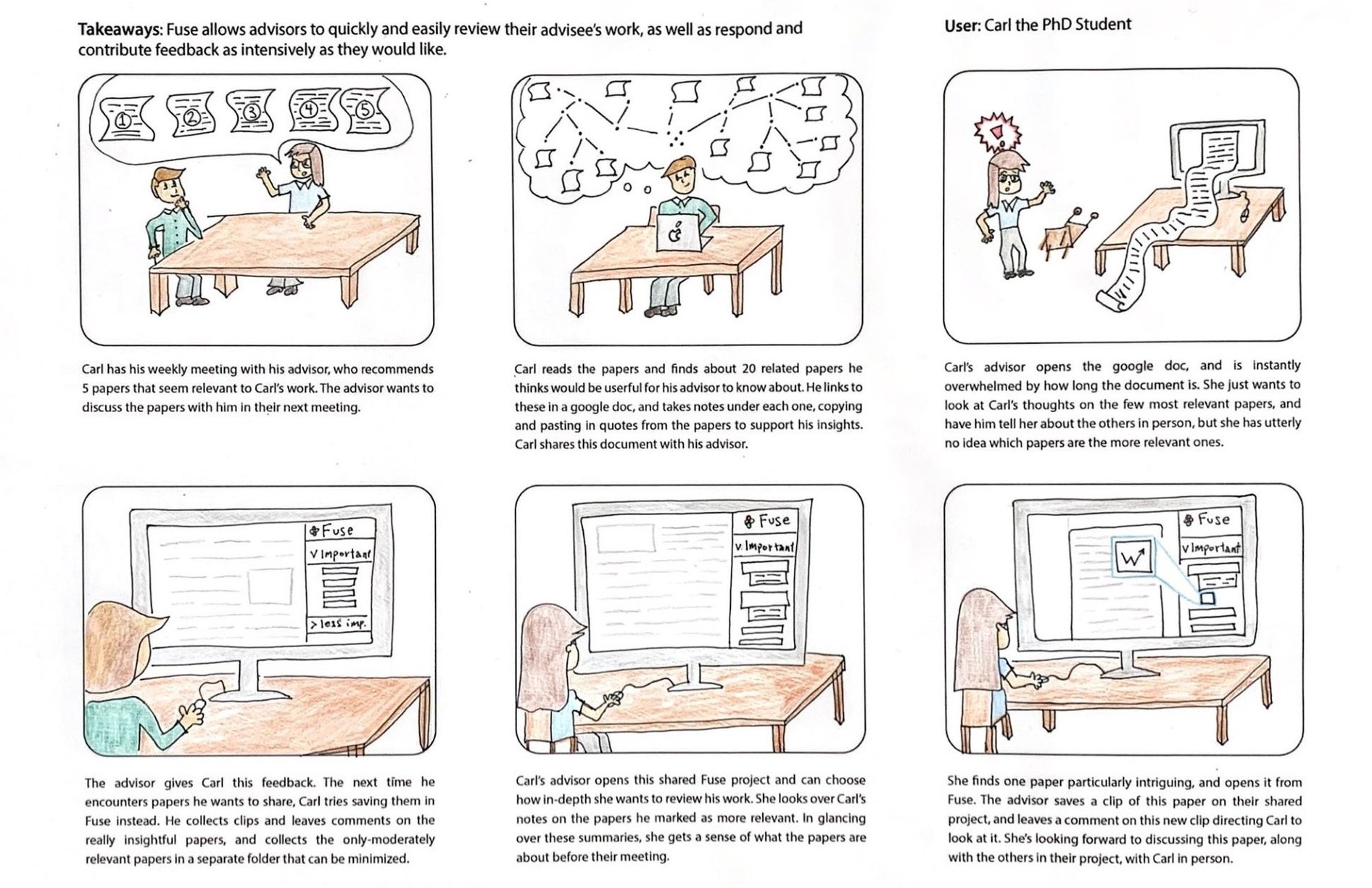

Storyboards

My work with storyboards aimed to explore the link between existing or prospective features and the value they bring to our users. To examine these relationships, I created a series of storyboards detailing common challenges that befall researchers. These storyboards illustrate the way Fuse allows users to tackle challenges using existing features, or how they could do so with prospective features.

After creating these storyboards, I conducted interviews with users to determine whether the problems presented were truly valid and disruptive, and if the proposed solutions were feasible and amenable. After holding these in-person interviews and synthesizing early insights, I designed and ran an online survey to reach a wider audience and learn more in relation to those early insights. Testing with boards showcasing existing features allowed us to discover whether these features were realistically used in the predicted ways. Speaking with users about the value of prospective features allowed us to prioritize these features’ development in accordance with real user needs.

User Research: Getting Information Out of Fuse

In past research sessions, our team had heard repeatedly from users that they wanted to get their information out of Fuse to use elsewhere. Although a sentiment we had noted many times across many interviews, no one on our research team really understood what this notion meant. With the sense that it was an important finding, but not a well understood one, I was tasked with further exploring it.

As my research assignment was only vaguely defined, I began by breaking down the overarching research question of “How do users want to get their information out of Fuse” into a series of more specific research questions:

What do users mean by “getting their information out of Fuse?”

What information do users want to get out of Fuse?

What do users want to do with this information once it’s out?

How does getting their information out contribute to users’ higher level goals?

Do users want to put this information back into Fuse?

I then designed an interview protocol that dug into these more specific questions. These interviews, besides a traditional question and answer format, included an observational process walkthrough.

After recruiting participants and conducting interviews, I synthesized my findings into the following two key insights documents. These insights were primarily referenced in my presentation of research findings back to the team. In addition, I wanted to ensure that insights with the potential to influence decisions made after I left the team would be easily accessible. With this intent, I designed the documents to be maximally skimmable and distributed them across the team for future use.

Click to enlarge

For the process walkthough, I asked users to take a source they’d saved in Fuse and go through the motions of moving it to a different application. This portion of the interview allowed me to catch parts of the processes the users themselves were unaware of, and therefore couldn’t describe. Insights from this particular portion of the interview were so valuable that I decided to capture them in their own document, shown below.

This insights document shows synthesized process flows for users methods of getting information out of Fuse. Most notably, these process flows allowed me to emphasize the tediousness of some processes our users were following in my presentation to the team.

Click to Enlarge

Key Takeaways from the Summer

Although my work with the Fuse team was conducted in an academic research setting, it often felt more like a startup environment with so many opportunities to jump in and lend a hand on many different aspects of the product. In this setting, I learned several meaningful takeaways that I know will allow me to better navigate future work environments and contribute to those projects with competence.

Flexibility is key for working in cross functional teams. In many of my collaborative projects for school, I worked with solely UX designers to create a final prototype that could theoretically be passed on to a development team. With Fuse, our designers and developers were exchanging information daily, and using feedback from each other to iteratively improve our work. With this structure, I grew to understand that the pure version of the User Centered Design process that my schooling has hammered into me isn’t realistically implementable, but that incorporating the key elements of that process is still valuable.

Good research design includes awareness of your own biases. Although I’ve encountered the mantra “you are not the user” in the UX community time and time again, in this case those of us creating the tool actually were the users. Fuse began as a tool to help academic researchers — those who make up the team working on Fuse — and grew into a tool for more general purpose research. This situation made it tempting at times to rely on assumptions drawn from our own habits, and sidestep time consuming user research showing how others do things differently. Rather than relying on our conceptions of “I do it this way and I’m a researcher, so all our researcher users must do it this way”, I made a concerted effort advocate for user research that ensured our product was accessible for a wide range of user workflows.

Understanding communication norms in the working environment vastly improves efficiency. As someone who really likes feedback, adjusting to an industry-like position without grading, peer reviews, and teacher comments was initially difficult. Throughout the course of the internship, I learned to feel out a balance between soliciting valuable feedback while respecting my coworkers’ and supervisor’s time. In communicating shared goals and articulating prospective projects in multiple ways, I also learned firsthand the value of ensuring that everyone is on the same page before moving forward with a project. In particular, honing this strategy allowed me to solicit meaningful feedback throughout the life cycle of each project and feel more confident about my work’s value.